Signposts

Escaping linear...and limiting...labels with Elisa Camahort Page.

"...the privilege to have the space to explore what is in between is really something we should value. When we can do it, we should appreciate it. Because when you are working hard just to survive, you do not have the space of 'in-between'." - Elisa Camahort Page

From The Noodler

As women, the "signposts" that define our careers are often formed by social and societal structures and narratives around work that can dictate or project unrealistic, uninspired expectations for how our lives “should” unfold. As we emerge from the pandemic, armed with perspective, many of us have come to realize we do not have to “return to normal” when it comes to outdated, broken and damaging career-defining labels and “norms”.

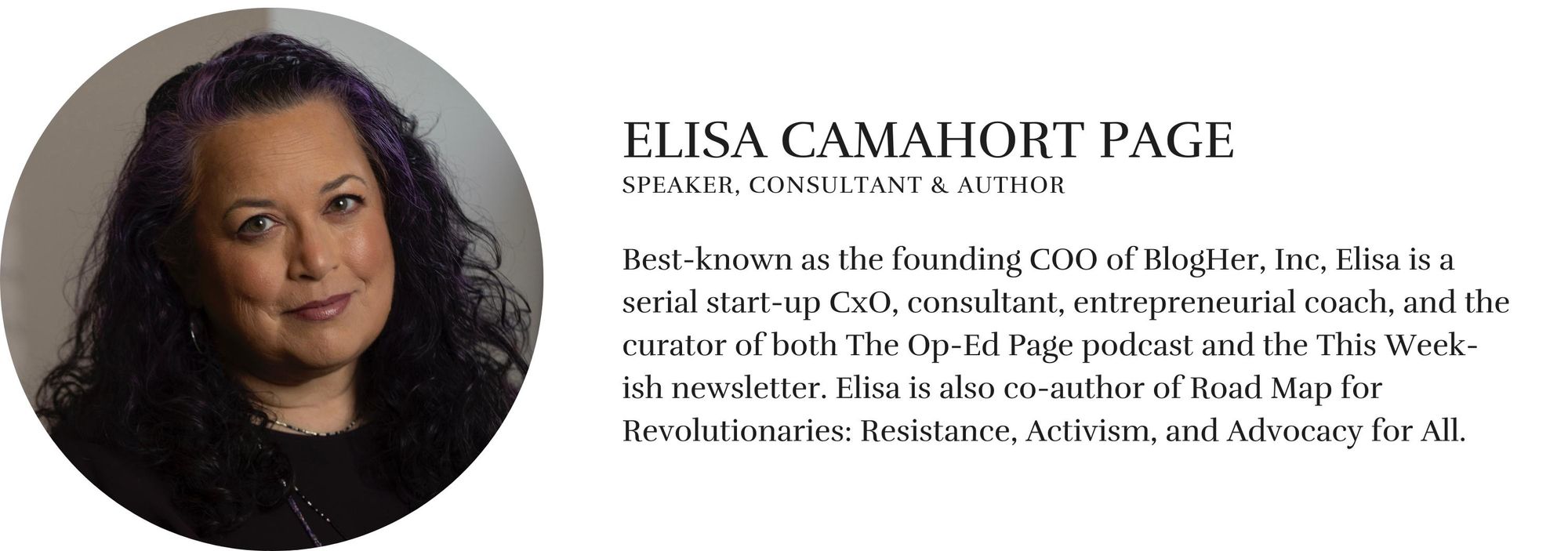

To unpack this, we spoke with Elisa Camahort Page to explore her personal journey along the road from "Girlboss", to "Badass", to "Inspiration", and her observations as an expert on the cross-sections of women, work, and advocacy - of how far we've come, how far we have left go, and the opportunity brought forth from the "liminality" of this unique time in history.

Listen

Read Along

Soft music plays

Elisa Camahort Page: You have to have the mental and emotional space to even allow yourself to think you want meaning and purpose...

Soft music continues.

Brady Hahn [00:10] Welcome to The Noodler, where we unpack timely cultural insights and quarterly digests. Featuring thinkers, researchers, strategists and creatives with an eye for contextualizing the present and forecasting the future. Our inaugural release explores what it means to occupy the literal and metaphorical liminal in our lives, along with some of the shifting cultural dynamics. My name is Brady Hahn, and joining me in conversation is Elisa Camahort Page. You may know her as the co- founder of Blog Her, Inc. The co- author of Roadmap for Revolutionaries Resistance Activism and Advocacy for all. As a speaker and as a podcaster. Many of you listening will also know her as a mentor and friend. Join us as we explore the signposts that define women's careers and the ways social societal structures shape our narratives around work along the road, from Girlboss, to Badass, to inspiration.

Brady Hahn [1:06] It's so great to be sitting down with you today. To start, when we first spoke about this conversation, you mentioned that you had written a post about wanting to use the word liminal more. What was the first time when you heard the term and what's drawing it to you personally?

Elisa Camahort Page [1:24] I think liminal is just a beautiful word. It has the L's, but it also has the resonance of 'M' and 'N' in the middle there. And it's three syllables like lim-i-nal. It's just a great word. I think I first probably heard it not that long ago. It's not a word I think I grew up knowing. It's not a word that in my career or academic background I used. I think I first heard it when I saw this fundraising crowdfunding effort for a bookstore. The bookstore talked about wanting to be that the community needed this liminal space. And I was like, oh, that's intriguing. What is that word? And has great letters in it. That was when I first kind of heard about it and applying it to a physical space. Recently I was at a conference and I heard someone using the word liminal to apply to a mental or emotional space. I wish I had written down the exact quote because what you're referring to is that I tweeted about, oh, my God, someone just used liminal in such a perfect way. And I love that word. And I've never had the opportunity. I don't think I've ever used it in a sentence, but I heard it and I was like, oh, I really like that word. Now, I've used liminal multiple times in multiple sentences here, so you've kind of made my dreams come true.

Brady [2:57] I love hearing that. Well - and it's funny, I kind of feel the same about the word in the sense that I'd never heard it, never really used it. Suddenly now I feel like it's everywhere of the moment. I'm curious, what are some of the ways you're seeing liminality in general play out in your life and work right now?

Elisa [03:18] Well, I have had another one of my favorite words, alert coming up. I've had a very peripatetic career

Brady: Good word! Good word!

Elisa: I know! And that comes from a chorus line, it's a lyric in a song. Anyway, I've had a very peripatetic career, meaning that I have jumped around up until a certain point, my career I had jumped around and done a lot of things. My first career, I thought I wanted to be an actor and singer, and I pursued that. When I was about 25, I'm like, I don't think I want this enough to justify the life it requires of people who pursue that. It's not an easy or secure life. At the age of 25, I had not prepared or planned to do anything else. It just left me completely free. I moved back to California after having lived in New York for several years. After college, I took a job in the commodities industry in which I had no background, no expertise, no education. Worked there for about seven years, and then I looked around and said, oh, I live in Silicon Valley. Maybe I should think about this tech thing in which I had no background, no education, no expertise.

[04:17] And I got a job in the tech industry and really had aptitude for it and took to it. From there I ended up co-founding BlogHer, with Lisa Stone and Joy Desjardins, and at that point I then sat still and did the same. I didn't sit still, but I was doing the same thing for the next nine years until we got acquired, and then another two to three years working with the acquiring company. And so, going from changing careers every five, six, seven years to being in the same space for twelve years was really coming out of that was a real shock to my system to think about going back to that kind of peripatetic life.

[05:03] And so, I would say since I left that acquiring company, I have gone through a lot of transitions, and each time I always joke and say I'm having one of my regular existential crises. I find I am interested in many things, I am passionate about many things, I feel moved by many things, and there are things I like and don't like about many formats and ways of working. I've gone full time to contract, to consulting, to coaching, to writing, to creating, and I've done all these different things. I always kind of feel like ever since that point in 2017, it's been what is that now?

Almost six years of I'm always kind of in between and I'm never quite arriving at where I think, oh yes, this is the me I'm going to be for the rest of my working life at the very least. And I'm in that space now.

I left a full time gig in December. I've been doing a lot of life stuff here in Q-One and I'm back in that, oh, I'm having one of my regular existential crises and I haven't found the thing I'm going to do or be for the rest of my at least working career.

Brady [06:22] Right. Well, the thing that I love about what you said is that in a way, it's like you've approached your life with liminal thinking. The fact that it's going to ebb and flow, they're going to be different stages and in a way that's still kind of a revolutionary way of living and working.It's certainly not what our parents and grandparents did anyway.

Elisa [06:46] For sure. I think most of us are not having the lives or careers that our parents or grandparents did in just every aspect. Things are pretty different culturally.

Brady [06:59] So different. I think that what's also really fascinating, though, is that you've had this flexibility of thinking throughout your life and career that allowed you to take those big leaps when you were in those in between kind of liminal spaces. It's not my background, it's not what I've done, but actually I think I can do it. Embracing kind of those liminal spaces to extend your life. I think it's kind of a fascinating reflection on how you can shape a career in a life that doesn't necessarily fit in a particular box.

Elisa [07:34] Something I say to people all the time when they're considering whether or not they should make the leap. I do call things making a leap a lot. I say two things, and the first thing I always say is you're much more likely not to actually like doing the thing you're considering more than not being able to do the thing.

Brady [07:55] Can you say that again?

Elisa

You are much more likely not to like doing the thing you leap to than to find out you can't do it. People fear I won't be able to do it. They fear failure more than they fear dissatisfaction. In fact, it's the opposite outcome, probably, that you're going to wind up.

[08:18] And the second thing I'll say is there are very few decisions that are irrevocable. You're not on a one way road to nowhere. You're on a road with exits, loopbacks, cloverleaf. There's so many turns that you can take. If you do leap and you don't like it, or you do maybe discover I'm not good at it, want to get good at it, because that's another thing I believe is if you wanted to get good at it, you would probably work and get good at it. So leap somewhere else or go back or try something new. Nothing is a life sentence.

Brady [9:01] Oh, I love that. I think there's a couple of things in that. One, we don't have the life that our parents had and therefore things really aren't a life sentence. We are living completely different lives than I think many of us even thought we would. But, I also love this idea of the chances of you being dissatisfied are so much greater than not being able to do "the thing". I think especially for women, we know, statistically speaking, that they are more likely not to go for a job because they feel like they don't check every single box or take the leap because of the fear of.... that kind of level of unknown about themselves. I think all of those things that you said are true. I'm curious, as a younger person, what do you remember about your impressions or expectations for a woman's life? Like the rites of passage that kind of stood out to you? Who or what had the biggest influence in shaping these ideas?

Elisa [09:58] Well, I think there's two different answers. I think very early, when I was younger, there was a brief time when I wanted to be a veterinarian. I got to high school and realized I wasn't that great at science, but also that being a veterinarian didn't mean I got to play with animals all day, but that sometimes I would have to euthanize them or operate on them or do sad things. And vets are among the most. They have a high suicide rate. Like, it's hard being a veterinarian. Not that I knew that when I was a kid, but I just kind of discovered in high school, like, no, I was not realistic about the physical, and I do not want to be that.

[10:39] And that's when I started performing. That's when I just decided this was going to be my thing. Singing and acting. I guess I had a plan. I was going to go to college because I was supposed to, but I went to my local. I lived at home and went to San Jose State. I saved all my money from working because I knew I wanted to move to New York. Once I was a freshman in college, I figured out that one of our professors had a relationship with a Summer Stock theater that gave young actors their Equity Card, which is the union card for stage actors. I made it my goal to be invited to go do that. I got invited and I went and did that because then I moved to New York with my Equity Card. And then, it stopped being something I could really set goals around.

[11:28] I mean, you just go to auditions and you go and you just see what happens. I didn't really have expectations. I think once I got there and realized, oh, well, I could engineer all of this to happen and move to New York with money in my pocket and relationships there because it's where my mom is from and my Equity card. And yet I couldn't. Engineer I could take the classes, I could go to the auditions. I still couldn't engineer or guarantee success. It's a low success rate field. Now that's one demarcation point. When I moved back to California and decided to work like real jobs as some people might, then my impression was entirely formed by watching my mom. My mom was a prototypical 1960s. She got married to June. She graduated from college and got married that same month. She moved all the way across the country to California where she didn't know anybody.

[12:23] She had three kids by the time she was 27 and she was a housewife. I don't my mom really liked most aspects of that. She liked to cook, but we did not get home sewn Halloween costumes. She didn't garden. I don't even think she really enjoyed who does enjoy? Some people I think do. She wasn't a housekeeper, enjoyed keeping the house particular. She really liked cooking. That was really it. She right away got involved in AAU and League of Women Voters. She was like super into community based.

When I was about ten or eleven, she decided she wanted to go to work and she started part time and she went from being the prototypical housewife to being the prototype typical career woman. She went up and up and up the career ladder. She became that first company's, first female VP. She stayed in the game till she was 70. She didn't retire until she was 70.

I just imagined when I started doing corporate work, I was like that was my impression. I need to just get promoted in advance, get a raise and promotion, get promoted in advance and like I am going to be a manager, then I'm going to be a director, then I'm going to be a VP. That was just what I thought one did until you retired. I guess.

Brady [13:54] I love that you had this mother who could role model though so many different aspects of what a woman was able to do and achieve in her life. It is kind of amazing that she really had girlhood marriage and children and a full career all within her lifespan. You've talked about the labels attached to women's careers and their success and there are these aspirational signposts along the way and which ones stand out for you and how do you see them working for or against women now?

Elisa [14:31] Well, I think an understanding that in my career for the last 20 years it's been a pretty entrepreneurial space and heavily in tech and media and internet.

The labels that I've really observed come to fruition and hang around are first of all, Girlboss. Second of all, you kind of graduate into being a badass, and badass is more I see it applied as frequently to corporate women as entrepreneurial women, whereas Girlboss is very entrepreneurial. You kind of just keep going over the hill until somehow you've graduated into you're a role model or an 'inspiration' or a 'mentor' or "a label" that comes with expectation of you're going to reach a hand back, you're going to give back, you're going to lift up.

And they're kind of attached to age. You don't see women entrepreneurs in their 50s being called girl bosses. Like, this is a label for women in their twenties and maybe early thirties.

[15:34] And then, you get a little more gravitas, which comes with more experience. It does align with age. You get to become a 'Badass' and then at some point you hit that. You're not expected to achieve for your own achieving. You're expected to achieve to lift up others. I just don't think there's an equivalent for men. I'm not saying we don't have labels for types of men, whether it's 'Masters of the Universe', a la Tom Wolf and "Bonfire of the Vanities", whether my favorite 'Tech Bros', or 'Tech Bro Dudes' - 'Tech Bros', 'Tech Bro Dudes' - I guess there's 'Young Guns' or 'Mavericks' or whatever, but these are often many of them are used kind of ironically or even pejoratively, and they are not used to try and typify a generation of men in the workplace. It's about a behavior or personality. It's individualized almost, whereas I don't know if women get to be so individualized.

[16:38] Attaching labels to a woman's career trajectory. It differentiates women's leadership. You can't see me, but I'm air quoting women's leadership and it differentiates it from simply leadership.

It constrains women, I think, from the same opportunity to be individualized that men have.

Let's say you're a woman in your twenties or thirties and you're not a girlboss type. I think "girlboss" has a type. We get this kind of dynamic and extroverted and glamorous. I don't mean that in a physical appearance way, but just like living a life and maybe a little provocative. Again, I don't mean that in a sexual way, I mean like provoking out there. But let's say you're not that person. Let's say you're awkward, let's say you're introverted, let's say you're nerdy, but you're a young woman. If you were a man who was awkward, nerdy and introverted with a great idea in your twenties or thirties - you'd be pattern matched all the way to like a super high unsustainable valuation.

[17:50] I don't think you see right now the same outcomes for women. They are going to be struggled to be heard and to be valued because they don't fit this narrative of who's going to be successful. I guess that's my point about the labels is that it narrows down and constrains the pattern matching. Pattern matching so often leads to support, to advancement, to opportunities, and to success. I think our possibilities are constrained by these labels. Ironically, I think that early in the days of blogger, actually, some people would say, well, I'm not a woman blogger, I'm just a blogger. I'm not a woman CEO, I'm just a CEO. My response always was it's great that you think of yourself that way, but when you sit in a room with 90% male investors or male customers they are well aware that you are an unusual atypical woman CEO or that you're a woman salesperson or whatever it is.

[18:59] So, you can want to issue that label but it is being applied to you. I just think at the time I think our philosophy really was how can we try to power up? If we're going to have the attached then how can we kind of power it up? Lastly, that whole inspiration role model give back. I just don't know if men are expected to do the same. They kind of have the old boys network. That's the way they are expected to take people under their wings and have proteges which are all really success oriented and help them get theirs. The problem I see with expecting women to be like these in general do good, give back folks once they get to a certain point and I spend my life doing that.

The problem I see with that is it's still looking to ask women to fix what they cannot fix because women cannot eradicate sexism or misogyny. It doesn't matter how much we raise up other women, the system of sexism misogyny, the system of patriarchy is still largely built and in control of men. They have to be involved.

[20:14] And this is true of any overlooked or oppressed group. Black people can't end antiblack racism. What I mean by that is to say there is no behavior, there is no action that groups can take to eradicate biases about them. They cannot act respectable enough, they cannot act any particular way that people will say, oh see now that they're all acting this way we're just going to get rid of these ingrained systemic biases and we're going to get rid of this system that we built. That is not how it works. We still rely on the people who built the systems to be a part of breaking down the systems. That's again why I think these labels can harm more than they help because they're also putting an onus on the people who are less empowered to do something about these systems.

Brady [21:12] Yeah, absolutely. I think what I hear from you is one, men get to have their careers defined by things that are based on their literally just doing their jobs where it feels like women have to perform to a certain degree or position themselves in a certain way in order to show their greater value to everyone. And I think it's true. I've spent over 15 years in professional development spaces and conferences and women are always kind of siphoned off into rooms where they're meant to talk about mentoring the entire room of people and sharing how to live your life in balance work where I think men get to quietly mentor other men. Like, it's more of pulling them one person under their wing and showing them the ropes and how to navigate the world where women are expected to do it on a large scale all the time.

Elisa [22:24] I've been to countless conferences where I am asked to speak on the Getting More Women in Tech panel or the Work Life integration. They don't call it balance anymore if they're smart integration panel. I'm like and there is more than one conference where I've said, I want to talk about my business. I want to talk about my expertise. If you don't have a place for me to talk about that, I don't want to speak about these other topics anymore. I've done my time, and they don't have me speak about those other topics. They want me to do the do good, give back, collective, communal, let's rise all boats. And I believe in raising all boats. Can I also talk about what blogger accomplished as a business? Is that okay? No, it's not. My experience is I know it's really not what people want to hear about.

Brady [23:16] Well, I think it's what conference organizers think people don't want to hear about because women actually, when surveyed, do want to hear about case studies and how to for businesses, according to surveys.

Elisa [23:29] Yeah, but if you're talking about a conference that has men and women, they assume that it's okay that women only hear from men about how they built their business.

Brady: Absolutely. Absolutely!

Elisa [23:41] And we should walk with our feet. I do vote with my feet. I'm just not interested in a panel that's 80% men telling me what they did. Like, they haven't lived my life, they don't live my reality. Why would their advice be their advice is great, but I've heard it like, literally a million times. So I'd like some different advice. I also think there is that research that shows that McKinsey and Lean In did about it's actually a myth that women don't ask for promotions or raises or things like that. Women ask - they get shot down more often, but they identified. I remember so clearly going to a presentation about this at Stanford University, where I think Cheryl at that time, Cheryl Sandberg - was still, like, presenting part of this. She said something about, I wish this wasn't the case, but the data shows that women are more successful when they tie something they want for themselves to why it would be for the greater good of the company or the organization. What is the communal benefit of treating her as an individual? Better. I'm just like it's just more hoops. That's the thing.

We create more hoops, more parts of our brain that have to be allocated to solving for biases instead of solving for the actual business problem. That's what every underrepresented, overlooked, or marginalized group has to do they have to give a part of their brain to trying to figure out how to navigate in and around in the biases instead of fully to the problems they want to solve. And that's the real problem with it.

Brady [25:15] Absolutely. I think further, it's interesting how the signposts that you've mentioned of womanhood and work are these personas that are deeply tied to our individual and collective sense of our relevance and power as women. One example you led research for She Knows Media about six years ago, focused on the “F" word - feminism - and gave some interesting insights on how women think about their own relationships to feminism based on their life stages. Can you share what you learned?

Elisa [25:51] Yeah, I think the big picture, unfortunately, indicated that feminism was basically sold as something that would bring tangible and primarily financial benefits to individual women. Therefore, I think our research uncovered that people - and women specifically - tended to relate to the concept based on their current conditions and whether it was serving that purpose for them. So what do I mean by that? For example, when asking about how women resonated with the term of being a feminist or not a feminist, we found that women who were just out of college, they didn't really identify or resonate with the term feminists. Well, women have been the majority of college students for a while now, and women do better in school right now. There's actually a lot of concern about boys in this country because women are just outpacing them, and so they hadn't really seen even though there are barriers in academia, it starts to happen more when you're getting into the graduate level. Early out of bachelor's degree, 22, 25, 26, they don't think feminism for them because they don't think they need it. You survey women who are a little older, who've been in the workplace, let's say five, six, seven years now, they start to resonate a little more with feminism because they're seeing exactly what they didn't expect to see, which was barriers and blocks and weird treatment.

I remember when I would talk to my mom about my career, and she would be just like, I just can't believe this is what my generation fought for. I just can't believe you're still having these problems. And I'm like, well, we are.

Feminism begins to resonate more, and then when women get into the premier work life, juggle age 30s into early 40s, feminism, again declines as something that they find important in their life, and that's because they've got all these other things they've got to worry about, and feminism isn't high on a list of overflowing responsibilities. We see an uptick again, because as women get more and more senior, they realize they're hitting glass ceilings or they're being sent over glass cliffs, and they realize, oh, s***, I read about this - this is happening to me too.

Labeling feminism as something that is largely about career advancement and maybe even corporate advancement doesn't really serve the purpose of people understanding that there is all sorts of other things that come with understanding that feminism is about equal rights for women.

[28:20] This is why bodily autonomy is totally at risk. Individual advancement doesn't equal justice. If we can't acknowledge that a non patriarchal society would make life better for everyone, if we don't acknowledge that the benefits of feminism are about broader equal justice. Now, men who identify as feminists, it seems like it's because they're doing something good, it's charitable, like it's giving them cookies, but it could be something of self and societal interest for us all to believe, to smash the patriarchy, basically. All of this to say, I'm not a gender determinist. I think the other thing that happens is we take this kind of feminine leadership concept — and we attribute qualities to feminine leadership versus masculine. We are socialized - I don't think those are innate qualities. I've been told I manage like a man many, many times, and I don't. I manage like me. We are socialized from a very early age.

[29:29] Men and women are rewarded and incentive very differently. The problem with this is that the qualities that are assumed to be masculine are in general more highly valued by more people when it comes to the world of the professional world. Right now, people are kind of championing the need for feminine qualities. Right now, there's like a movement to say, quote unquote, soft skills, which I just call leadership skills are important. As soon as we distinguish those as being, oh, now I think there's a book somewhere called The Athena, something about feminine leadership, right? I'm like but by setting it apart like that, we are reinforcing hiring and fundraising biases, and we are letting leadership and women be subject to fads and trends that can go away. We are not the foundation. We are this extra thing that right now people say they care about. But how long will that be?

[30:40] And I also think - I'm sort of jumping around here - I also think it becomes a lot less relevant because the younger generations today, they have a much different, much more fluid understanding of gender.

Now you have a generation of people coming into the workforce that just don't think of male and female and masculine and feminine in the same way. And you're just going to b*** up. You're going to b*** up against all these assumptions and biases and built incentives against a generation that just doesn't see gender in this way.

Maybe as this generation takes over, we'll get past having to call out our gender, having to recognize gender as a factor, having to lift up by gender, because maybe they'll eradicate some of those structures that have made that necessary.

Brady [31:28] We could hope so, right?

Elisa: We could hope so, yeah!

Brady: It's interesting because I think - circling back on the research on feminism that you found is like, to me, I always felt that it was a set of values that one holds, and for some, it is a large part of their identity. The idea that one's feminism would be a straight line seemed really natural to me and increase with age as women cross more of these obstacles and gain confidence. I think this also shows, to your point, other points as well, like why we need more research and deeper discussion about women's lives and women's lives as a whole and not just in comparison to men and men's careers. Also looking at the nuances of women compared to other women, because I think our lives are more than just like, that kind of binary comparison of the two.

Elisa [32:25] Well, what the comparison does is I've often heard women say that they didn't like their women bosses and women are hard to work for. People used to say to us all the time at Blogger, they were amazed that three women could co-found a company and stay together and run the company together for nine years. First of all, there are not that many founding teams that make it that far of any gender mix.

Brady: Period. End of story. Yeah, totally.

Elisa: There's two things I always say about that. The first is that, well, often most people have had more male bosses than female, and men get to be, again, individually crappy, whereas women are representatively crappy. I always ask people, like, if they ever had a bad male boss and did that mean all male bosses were bad? The second thing is that in a world where many companies are, you can see who's in leadership. You can see it's all, like white dudes, except there's one woman, there's one man of color, there's one like, there are people who get propped up to make the company feel like they have representation. It's rational to think, oh, so my competition, if I want to advance, is not everybody.

[33:38] I just got to be identified as that one woman star and every woman who makes it to, like, the C suite. I think things are changing. I don't think nothing's changed, but certainly in my days in corporate tech, every company had, like, the one woman who got to be the star, and you had to be the star to really and so, yeah, it was rational to be like, I just need to better than all the women. I need to be the woman star.

If you are ambitious, and it's okay for women to be ambitious. I see there is something extremely hyper rational about sense of competitiveness that women have gotten in the workplace from other women. We are a product of our systems and environment, and so it makes sense to me.

Brady [34:26] Yeah, absolutely. For better or worse. Awareness, I think, is part of the key and understanding where the behavior is, where the actions stem from. On a personal level, you mentioned that there are additional social signposts and expectations with each decade, and that measuring in decades applies a kind of pressure that doesn't necessarily align with the reality of how women live their lives because they're not linear. Can you share how your life experience has drawn you to reshape this narrative and moved you to develop a deeper appreciation for the small time frames, the weeks, the months, the years?

Elisa [35:10] Well, like I was saying earlier, my early role model was my mom, who did take that linear approach. This was back when her kids at the time were probably about 1311 and seven and were latchkey kids. That was certainly acceptable at a younger age than I feel like it is socially acceptable to do now. Her career started, and by the way, she was super young still. She was probably 35 when she got started.

Hers was a very linear career because I think it mirrored men in the workplace because she was a rare second wave feminist getting into the workplace. The problem is that's not how our lives really work.

It is hard to be successful at scale as women, not as a woman, because women still bear the load of a lot of outside the workplace life things. Caregiving for kids, caregiving for elders, dealing with the whole family's health and wellness, all of these things that create this ebb and flow of what a woman is still more responsible for than if she has a male partner. It's hard for us to have linear careers at scale as women because this is still how society works.

I remember I used to get really depressed and hate turning, like when I turned 28 and 29, 38 and 39, even maybe 48 and 49, because I felt like, oh my God, my 20's are running out.

[36:58] I only have a little bit of time left to do what? I don't know - what did I think was only going to happen? Did it within my 20’s or my 30’s? I always actually felt some people really hate turning like 30 or 40. I always like, Yay, the start of another decade, I have ten more years to do what? Again, I don't know. I don't know if it had any meaning, but I really have that mentality that 30 was the start of my thirties, and I had a greenfield ten years to be Girlbossy and Badassy or I don't know what. I'm turning 59 actually, in a couple of weeks. I'm like, I've been thinking to myself, I should actually do something big and fun for 59 just to celebrate that for once this year. I'm not approaching 59 with dread. I'm like, it's just a year. Like, it's a completely meaningless - I don't know what I was thinking, but I'm not the only person who looks at just like objectively, it's a number of years. It doesn't actually mean f*** all, basically, but I would really let it affect my mindset.

Brady [38:12] I think - this makes me think about a couple of things. One, our individual and collective perception of time and how much that plays into moments that stand out in our lives. The things that are incredibly joyful, incredibly painful or challenging, like you mentioned, caregiving. When things like that come into your life, days, weeks, months can feel excruciatingly long. It's interesting though, how the weight of our memories, like, in our bodies and in our minds can have all those things weighed the same, even though they're entirely different in our lives. Milestones like getting a new job or receiving accolades for projects, things that feel so monumental when they're ahead of us can feel like blips in our timelines of our lives. I think the pandemic as a whole seems like an obvious collective kind of liminal experience that we're still in, that we're still kind of unpacking and resolving. How have the events of the last few years impacted and reshaped all of these dynamics from your perspective?

Elisa [39:21] I think the last three, but I might even say five, eight or even twelve years have been pretty cataclysmic when you think of societal impact. It's an increasing trend that people of all genders, by the way, this is not a gendered thing, have expressed more and more need for meaning and purpose. Like why am I here? What am I doing? What meaning does my life and my work have?

One of the most interesting pandemic outcomes was that people across income strata were really for the first time, freed up, both by the time freed up by lockdown by, let's be real, lots of businesses shutting down, even if temporarily, and schools shutting down, and activities shutting down. You couple that with the fact that we basically had universal basic income for a year and child rearing financial assistance offered by the government, both those things happened and people of all income strata were able to think about meaning and purpose.

Typically it had been reserved for more privileged groups who got to do that. We're all kind of plunged into this existential limbo. We were all in this liminal space together, wondering what was next and really not knowing what was next. I was just saying this yesterday to someone. People left stuff at their office or at their school thinking they'd be gone for a week or two weeks and two years later they went and got it.

We all got plunged into this and we all have to think about, well, what was work in life going to look like? What do we want it to look like?

We all got to think about that without worrying about being evicted, without worrying about - for most people - there were so many resources. Did every person in every group access the resource and get the resources? No. I'm sure many people fell through the cracks, but you were not going to get evicted, you were not going to starve. There were food programs for the elderly, food programs for the shut-ins, food programs for everybody, and you didn't have to worry about that. If you got COVID, you wouldn't be able to get treated. COVID treatment was free. Right? All of a sudden you have this weight that we have, this weight of uncertainty and fear and doubt, but we also have this weight lifted of the immediate - you didn't have to pay your student loans back. You still haven't had to. Right? Student loans have a huge impact on the decisions people make.

[41:48] What was a shock to our economic system, which is based on patriarchy and white supremacy? Let's just be real. What was a shock to that system was to discover, hey, those low wage workers that we don't even pay a living wage, who have to get food stamps, even when they're working full time at a store or a restaurant or whatever it is, they don't want to come back. They're not begging to get those back breaking jobs back that didn't even pay them a living wage.

People want to say, oh, people don't want to work. No, people realized, oh, I don't want to kill myself. I am worth more, I have more value as a human, my existence is more valuable than this. We keep talking about going back to normal. Normal at its core was so unequal.

We could have looked at what we did during those first few, couple years at the least, of COVID and say, what did people do when there was this true existential threat?

[42:52] People dying, we could try to engineer for. What could we do to continue to give people that possibility?

People are very eager to return to normal, where only the privileged among us are allowed to stay in that limbo transitional moment, figure out what would bring us more purpose and meanings that our lives - but really all human lives - call for.

I think this has been a shock to people at all levels of the system to realize when you're not working all those jobs and you're not killing yourself and your body isn't aching every minute from the jobs that you're doing, a lot of people probably were like, oh, I do want meaning and purpose.

You have to have the mental and emotional space to even allow yourself to think you want meaning and purpose. When you're trying to survive, it doesn't help you to say, "I want meaning or purpose." It feels like cruel almost.

[43:50] And we're going to have to reckon with that. I don't think we've really reckoned with it. I think we all just think, oh, we could go back to that I'm like, I don't know. I don't know if that's a lasting thing that we're going to be able to do and go back to the way we treated people in the unequal system.

Brady [44:08] Knowing all of this for you, do you see liminality then, as a positive, negative, neutral, or does it depend on the context?

Elisa [44:17]

I see liminality as a privilege because I think it's what I just said, like, if you're trying to survive, I don't think you get to experience liminality. You don't get to experience it physically. Like you are trying to figure out how you survive, but you also don't get to experience it mentally or emotionally."

You do not have like I don't know. I just remember reading "Nickeled & Dimed" years ago now, and just the way she so clearly illustrated how hard you work to be poor. It's so much hard work. And so liminality is a privilege. When I said earlier about how our brain space gets carved up and I think people also don't realize how much brain space goes to navigating being in spaces that weren't made for you, in spaces that don't necessarily welcome you, in spaces where you feel belonging, the navigation, and what kind of wasted brain space that is. I think that I always say for people who don't understand, for people who say that people are always trying to play the race card or that sometimes things aren't about race. I'm like for women, I always say, think about your time in the workplace and all the little microaggressions about being a woman in male dominated spaces.

[45:53] When the MeToo movement happened, I went back and looked at my whole career and said, oh my God, the s*** I put up with - that I tried to laugh off, defer, wiggle, wriggle out of literally sometimes the stuff I did. I just didn't think of it as quote unquote, that bad. It made me relook at a lot of my experiences. Oh, God. That's terrible. Why was that okay? It wasn't okay, but I just took that as a price of doing business, right? So, as women, if we can think about and know that every time someone held our hand too long or hugged too close or even looked at us in a way that was clearly a Lear or even onto much more extreme things that happen, obviously. Or we knew the time that were interrupted, or when someone took our idea, or when someone didn't ever even ask us for our idea, or when we're told were too direct or aggressive or obnoxious for behavior that a man would have been assertive and awesome.

[46:54] All the things, all the things. We know all the things. If all the things and you can sense when some people you don't mind giving a hug to some people you don't mind having a really vibrant interruptive, you're mutually interrupting each other having a really dynamic conversation. You just know when it's inappropriate, when it's uncomfortable, when it's a microaggression, when it comes from bias. You know, and if you know that in your life as a woman, why do you think any other underrepresented group, whether it's color, whether it's the LGBTQ community, whether it's the disabled community, why do you think they wouldn't know when they couldn't sense the same exact thing, that this is a microaggression? This is coming because of who I am, not what I do or how I produce or what I offer.

All of this to say that the privilege to have the space to explore what is in between is really something we should value. When we can do it, we should appreciate it. Because when you are working hard just to survive, you do not have the space of "in-between." To ruminate about and think about and feel all your feelings about. It gets compressed into a tiny, tight little ball of - a ball of dissatisfaction, of the thing that can't scratch the wish you can't fulfill.

So that's how I think of liminality.

Brady [48:34] What do you see as moving towards, or what would your hopes be?

Elisa [48:38] I think that we have to continue to mobilize. Like we can't escape this. Last year, I would say even the 2022 elections, I felt tired. I felt like, oh, I last seven years being so hyper mobilized, so hyper focused for so long, and I felt really tired, and I felt like I just couldn't give as much. That's a privilege, too, that not everybody has to say, oh, this year I just can't do the same things.

I always think about the term patrice Colors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter. When I interviewed her for my book, she talked about the concept of not self care, but collective care and really taking care of ourselves and others and allowing the same from others. I also think of that metaphor of the choir.

When you have a really long note of the choir, not everybody can just hit that note and hold it forever. If you all breathe at different times, you can sustain the sound.

I always think about when I would speak about my book, Roadmap for Revolutionaries, I would talk about the number one thing to do is triage and assign yourself the one or two topics you care about most to really be a leader on. For all the other things I care about, which are many, you have to be like a supporter.

[50:10] You have to let other people lead and activate when they tell you to. I think we really need to continue to grow collective care and community care so that we all get the chance to have those liminal spaces, so that we all get the chance to rest, but that we make progress towards a goal of a more just society. I continue to really think about if all of us who were not served by the current systems worked together and didn't allow ourselves to get drawn into conflict, we would be so overpowering.

That there are a lot of forces that want us to be in conflict. It's hard, but without it, that is my hope, is that we can ever move forward towards working together and collective care and community care and taking a breath while other people sing around you and singing when other people need to take a breath.

Brady [51:15] Elisa, I want to thank you for this wonderful conversation and your thoughtful insights. Where can we find more information about you and your projects?

Elisa [51:26] Yes! So my website is Elisacp.com and that's my professional work. I have a substack.com and that allows commenting like old fashioned blogs. Like, I write newsletters there, but also you can go comment on the newsletter. It feels like a blog to me. My podcast is the Op Ed page with me, Elisa Camahort Page, and that's everywhere podcasts are. I'm @ElisaC on Twitter, which I'm phasing out because I ain't going to pay for that blue check that has never got me nothing. I'm @ElisaCP on instagram. I'm @ElisaCP on TikTok. No matter what they're spying on me about, like, I love me some TikTok. I'm trying out those other tools, the spottables, the mastodons, I'm trying them, but I'm not sold yet. Those are all the places. I'm in many places - talk to me anywhere. I was a digital utopian back in the early aughts and we screwed it all up. We super f***** it up. I control and curate my own experience and who I talk to. I still have a delightful time on the internet every single day because I don't get drawn into all that other stuff.

Brady [52:48] Thank you again (soft music plays). And listeners, you can find the full transcript of this conversation and more from The Noodler online at thenoodlecollective co. Thank you for listening!