Wayfinding

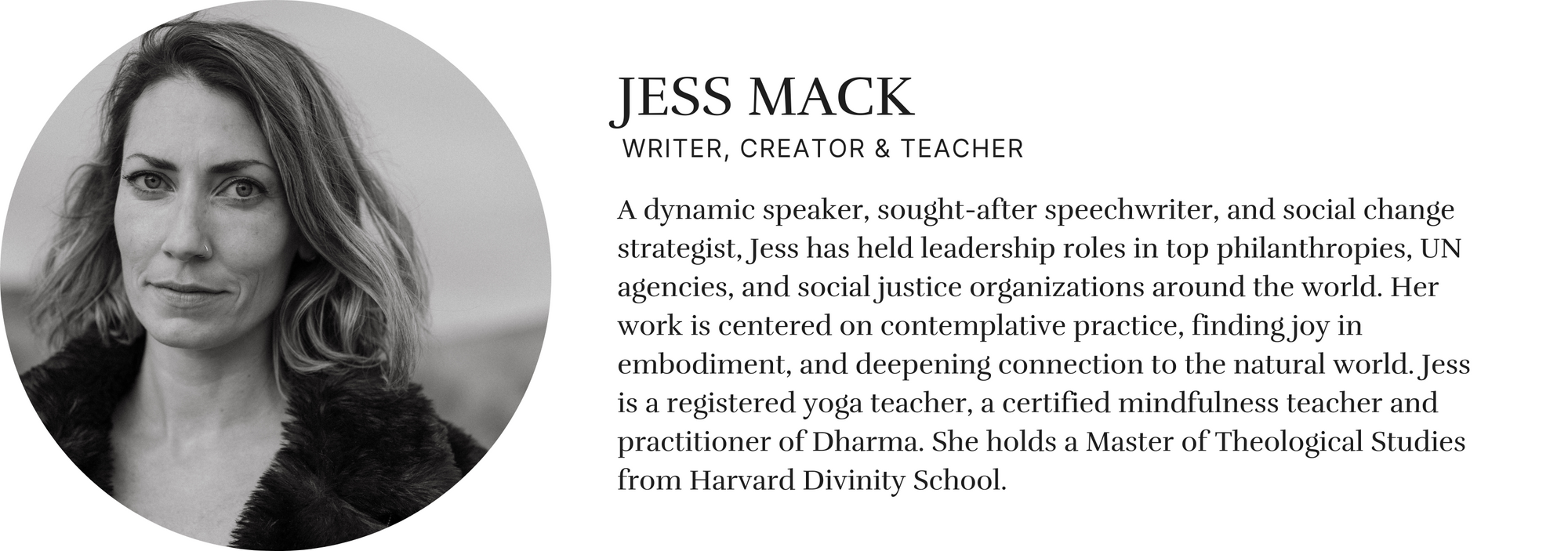

Searching as an act of devotion and faith with Jess Mack

"To search is to choose to be open and stay open. That is faith. To hold space for what you cannot fully fathom." - Jess Mack

From The Noodler

We are all on a journey to find our way to meaning and purpose. Searching for an understanding of what was, what is, and what will be in our lives is an act of devotion - one that requires great faith to usher us through transitional times - especially when things feel chaotic and unsure.

To better understand the journey of “wayfinding,” we turned to advocate, creative catalyst, and teacher of dharma Jess Mack. Jess holds a Masters in Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School with a focus on Buddhist Studies, in addition to spending her career focused on global reproductive rights for organizations like the UN and Planned Parenthood. As the author of Birdseed - Jess has made a practice of interweaving personal stories into a meditation on the “seeds” that appear before us as it relates to the philosophical search for meaning, our beliefs, and finding faith.

Visual Essay

For my fellow searchers everywhere, keep going. Although you already have what you need.

For my twelfth birthday, my mom gave me a silver braided ear cuff. It was as cool and beautiful as it sounds. Intricate but understated. A real feat of jewelry-making. A crisp three-quarter circle to smartly hug my tween ear.

I’d affix it in the mornings before school and though by third period my ear was red, hot, and a bit achey, it always felt worth it. Once you’re an ear cuff person, people start to expect that of you. Tré cool. Tré chill. You can't be deterred by a little discomfort. “Get over it, Jessica,” I’d think. “It’ll eventually go away.”

And one day, it did.

I was arriving to English class when I discovered the cuff had fallen or jumped from the ledge of my ear. Jettisoned into the vast, smelly world of my middle school. My stomach dropped. Panic rose. Then, determination. Fire. The scent. I will find it.

I had a vague sense of where it might be. The desperation in my voice lent me credibility to earn an open-ended hall pass from my teacher, and I was off. But as I rounded the corner to the hallway where my search would begin, my heart sank.

An irritating detail I’d not fully registered was the hallway floor’s frenetic pattern: something I could only compare to crushed fruity pebbles flecked with silver and teal. What?! It was hideous and dizzying. It was a vast, expert-level “Where’s Waldo” scene for a little cuff like mine.

I assumed the “I’m looking for something small” posture. You know the one: doubled over, arms clutched (sometimes extending tentatively into dinosaur claws) and neck craned, slow, heavy-on-the-heels shuffling forward, eyes scanning wildly.

I tried to be systematic and to stay positive, imagining myself as a big benevolent machine scanner that would for sure find the cuff. An hour slunk by. My body was getting stiff and my will wavered. I noted my ear felt painless and free.

The possibility that I might not find my ear cuff began to slowly creep over me as I instinctively reasoned with myself, gathering coping mechanisms from the practical to the spiritual. Maybe someone had found it and it was waiting for me in the lost and found. Maybe someone would find it and keep it, and it would bring them joy. Maybe losing it was “meant to be” – the universe or God or my mother teaching me a lesson on letting go, responsibility, or something else esoteric I had yet to even comprehend.

The longer the search dragged on, fruitless, the more I sensed myself lured toward acceptance. “Let it go, Jessica.” This 12-year old benevolent machine scanner powered down.

It was painful to think that my special birthday cuff from my loving mother might instead be found by the dusty, grisly bristles of a janitor’s push broom. That it might spend the rest of its days glinting somewhere in a landfill. But I guess that’s how we all end up anyway, if we’re lucky. I just wished my cuff could know that I searched for it as hard as my little doubled-over body and old soul could.

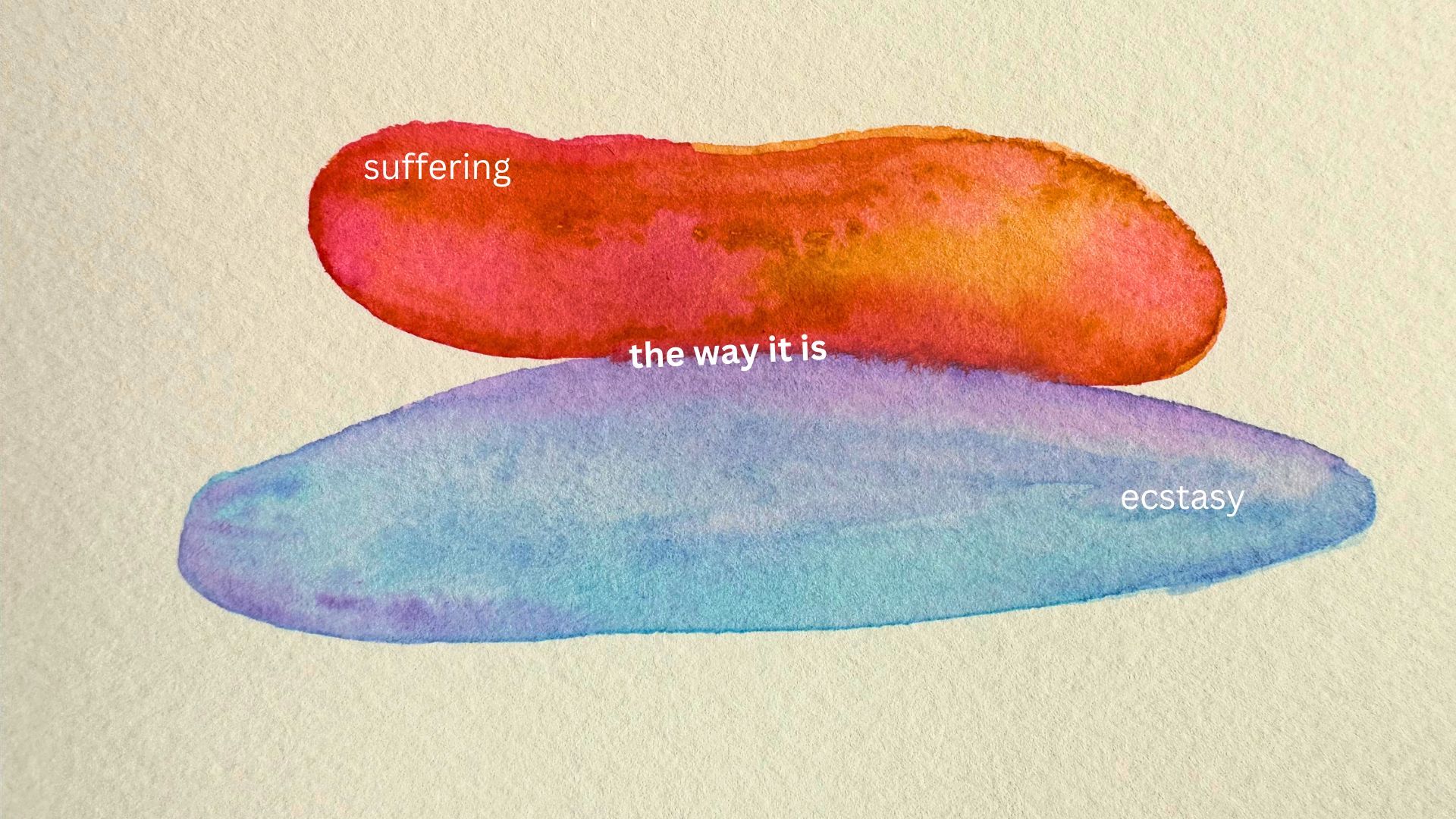

To search is deeply human. It’s a knife edge experience— an in-between.

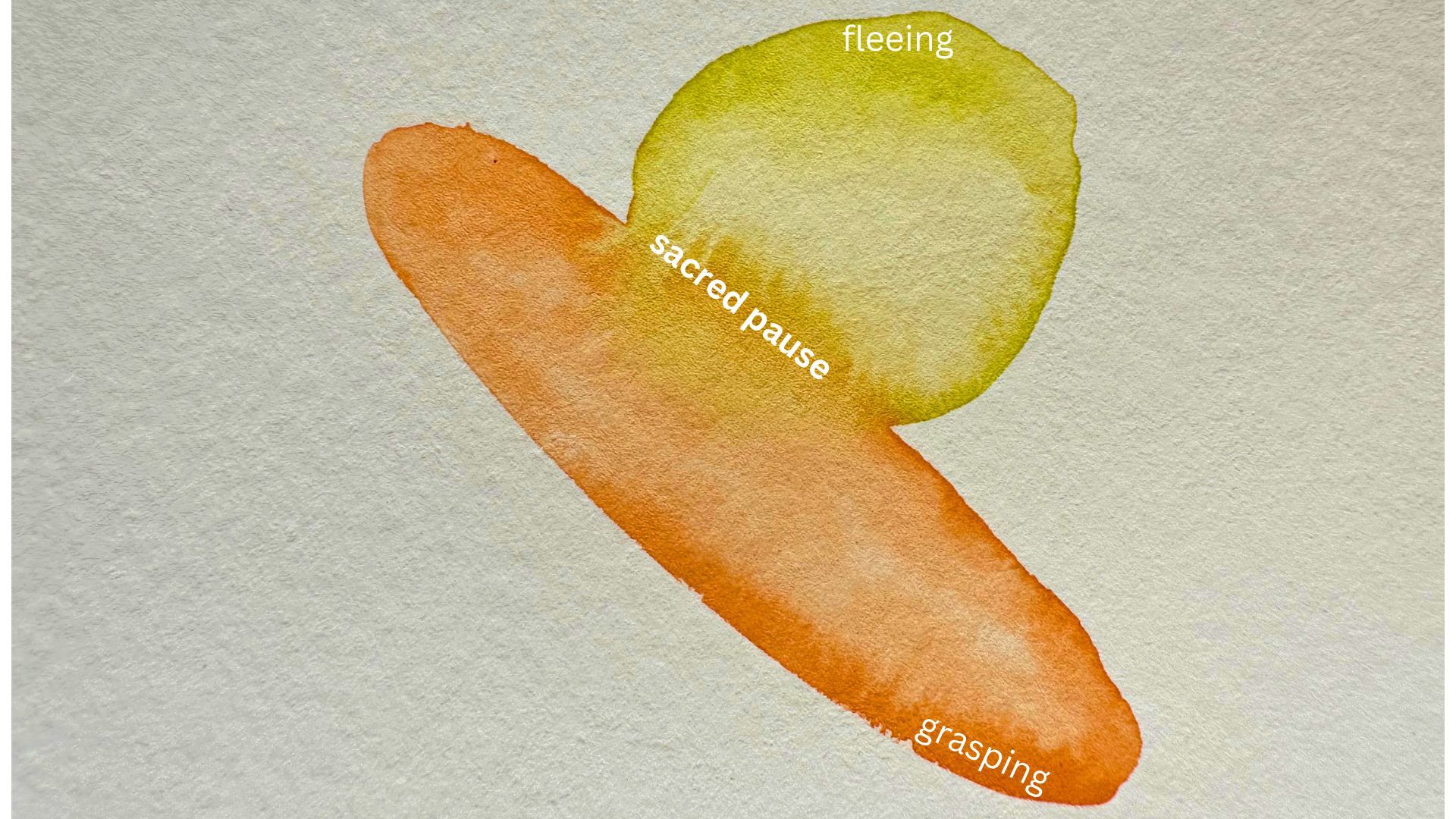

To search is to have the experience of having had and not having, all at the very same time. It is the poignant, often public, articulation of wanting something that you don’t yet or no longer (and may never!) possess. Confident and vulnerable at once, searching is a rainbow swirl of hunting, yearning, hoping, grasping, and waiting. You’re really all the way out there.

Not all searches are the same. They’re various shades of raw, but they’re always all our own.

There are our searches for the tangibles: ear cuffs and other silver braided sundries, the perfect credenza, an air-cooled Porsche 911 in cherry condition, that goat cheese you had that one time at Laura’s cousin’s.

There are our searches for sentience and particular sentient beings we loved, love, or hope to love: birth mothers and fathers, friends we’ve let go of or lost touch with, “the one that got away” or “the one” we hope is out there, missed connections, and beloveds taken or gone missing. Or we search for signs of life in the outer reaches of this beautiful universe.

Then our searches begin to fan even further out toward the esoteric, arcane, and beyond. Moving from the literal to the utmost dissipated and wispy. Searching for that which cannot be named, or we stumble to explain. Where language fails and our brain confounds. Meaning; a reason to live. Faith, god of some sort. A sign. Acceptance. Peace; to feel loved, be loved, to believe in love, to actually, truly love oneself. Searching to feel whole, or for arcane insight into this wild blink called life. Why the hell am I even here? Why are you here?

We’re all somewhere on these searches, and often in the midst of many at once. This is our very human practice.

You may be at the hopeful beginning. Full of potential energy like an egg about to be dropped off a ten-story building. Or drawn forth with great grief (they say nature abhors a vacuum). The pungency of a recent loss pulling your forth.

Perhaps you’re in the thick of it, at the full-fledged, frantic peak. Focused, purposeful, determined. You are sure you are just about to find it. You have to be.

Maybe you’re in the delicious moment of elated, incredible reunion and the deep blanket of relief that soon follows to wrap you up. Wow. Amazing. The search was worth it, you did it. It was there for you and you found it. Or it found you. Vindicated, rewarded, requited.

You may also be sloping toward the bitter end, losing hope or just now hopeless. Hopelessness, of course, not necessarily being a static state but something that flickers in and out.

You could be slowly falling backward into acceptance, surrendering to the possibility that it is or may be gone, or not (yet) yours to find - ever or in this lifetime.

You’re in the spiky, noble moment of throwing in the towel; and the grieving aftermath of not-having-found. Fuck. Now to contend with loss.

And then, you never know, things do eventually turn up. That will always hang in the air like a playful specter. You don’t know what you don’t know. Sometimes they annoyingly say that you find what you’re looking for once you stop looking for it.

Searching is a blizzard of choose-your-own adventures. Only some of it is up to us.

What is up to us?

Our hope; our effort; who we call in to our search party. The longevity of our search and the texture of it: the ratio of frantic grasping to spacious patience (“spatience”?). Our mindful devotion. Our ability to decide when it's really over. What’s up to us is our relationship with letting go. Acceptance that perhaps we’ve already found it.

What is not up to us?

Woof, a lot; everything else. Whether the thing is (or feels) found. What else we discover on the way. What else we find that we didn’t realize we were searching for.

To search is to choose to be open and stay open. That is faith. To hold space for what you cannot fully fathom.

In “Waiting for God,” the French Christian mystic Simone Weil compares searching for God with loving God. She, in particular, desires eventual, total obliteration in God. (Love that for her; to each her own!)

Finding God, in her estimation, does not result from fanatic grasping but a deep, spacious devotion. “Above all, our thought should be empty, waiting, not seeking anything, but ready to receive in its naked truth the object [God] that is to penetrate it” [...] “We do not obtain the most precious gifts by going in search of them, but by waiting for them.”

Here, waiting doesn’t mean casual apathy and tuning out. It means loving cultivation of space held. A spacious longing, perhaps nourished by the faith that, as Rumi *promises* us, “what you seek is seeking you.”

Faith is not tuning out or tuning in, but attuning.

I’m here to tell you that many of our searches will be unrequited. It doesn’t mean the search is pointless or our energy wasted. Even if what we seek is, indeed, seeking us (turning a unidirectional hunt into a multidirectional collision course), that doesn’t mean our orbits will cross in this lifetime or any other.

The search itself becomes an act of devotion, a practice of openness, ritual, awakening. The search itself becomes evidence of our very human existence - so goddamn precious and fleeting.

In theology, apophasis, or negative theology, is the idea of finding through continually not finding. Or describing that which cannot be described by affirming all that it is not. Like when you invertedly raise a subject by saying “not to even mention the fact that blah blah blah.”

It is possible to gain a deeper knowing of that which you seek – a finding, in a way – through the continual practice of seeking it, longing for it.

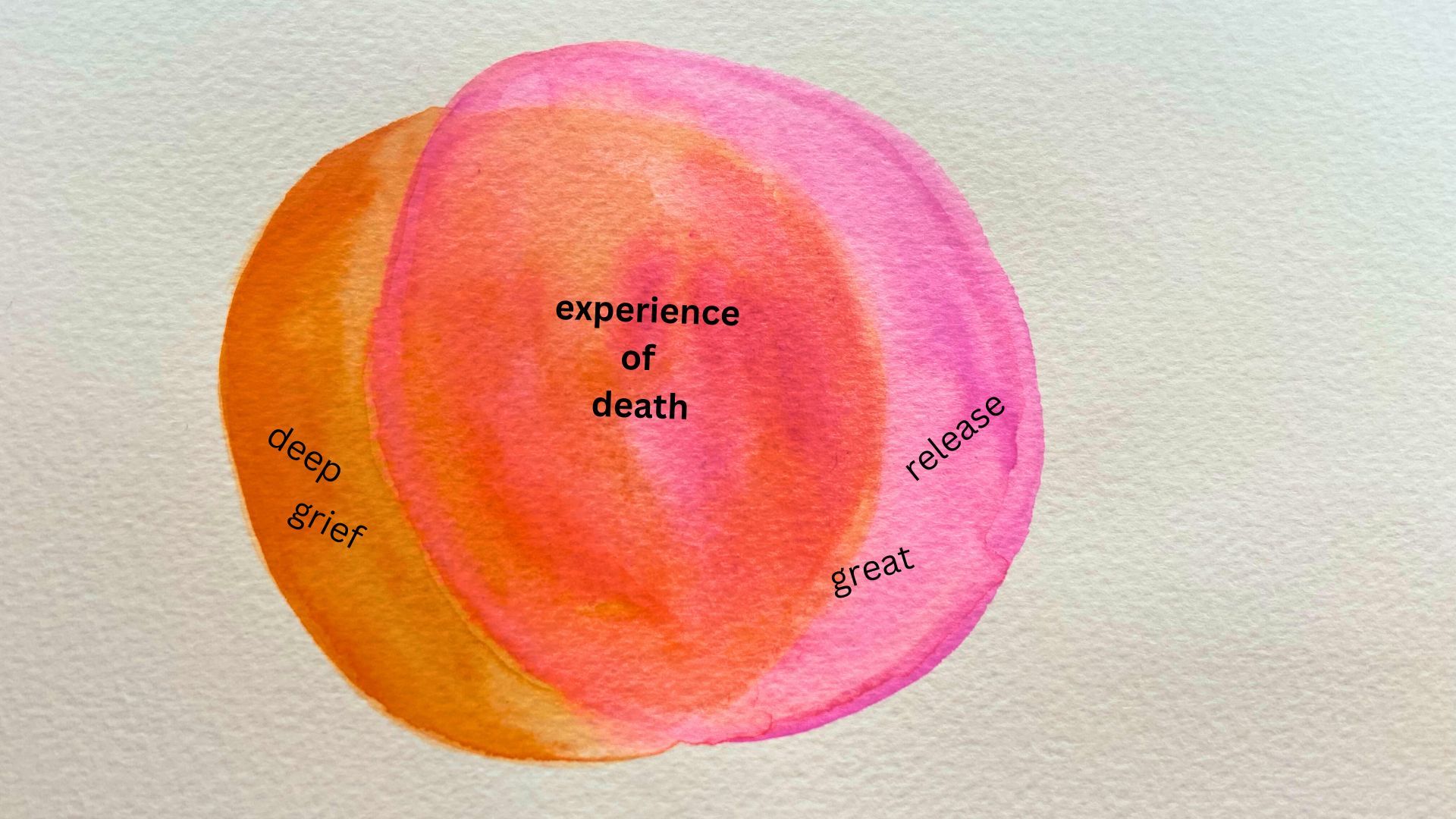

Grief can be like this. How much deeper and more expansively do we know our loved ones once they are gone?

In Buddhism, the concept of samsara describes the cyclical suffering nature of our existence, propelled in large part by desire and ignorance. We want things or people to be a certain way, or stay a certain way; we want to have and keep things; and damn if that isn’t just ever how it goes. Or it is then it isn’t. One day you’re an ear cuff gal and then you’re a nobody.

The more we seek and grasp, the more we lose or perceive loss. This sum total begins to feel like an agitating suffering that never ends. Our searches become great weighty chips on our shoulders rather than spacious, inspired journeys forth.

If you suffer or have suffered in this lifetime, you’re not doing it wrong and you’re not alone. It’s just not all that there is – deep down you know this. Eventually our experience of samsara ends (possibly) with our inevitable death (this, for sure, will be your fate). After death there is….? Unknown, or depends on who you ask, or depends on what you’re looking for.

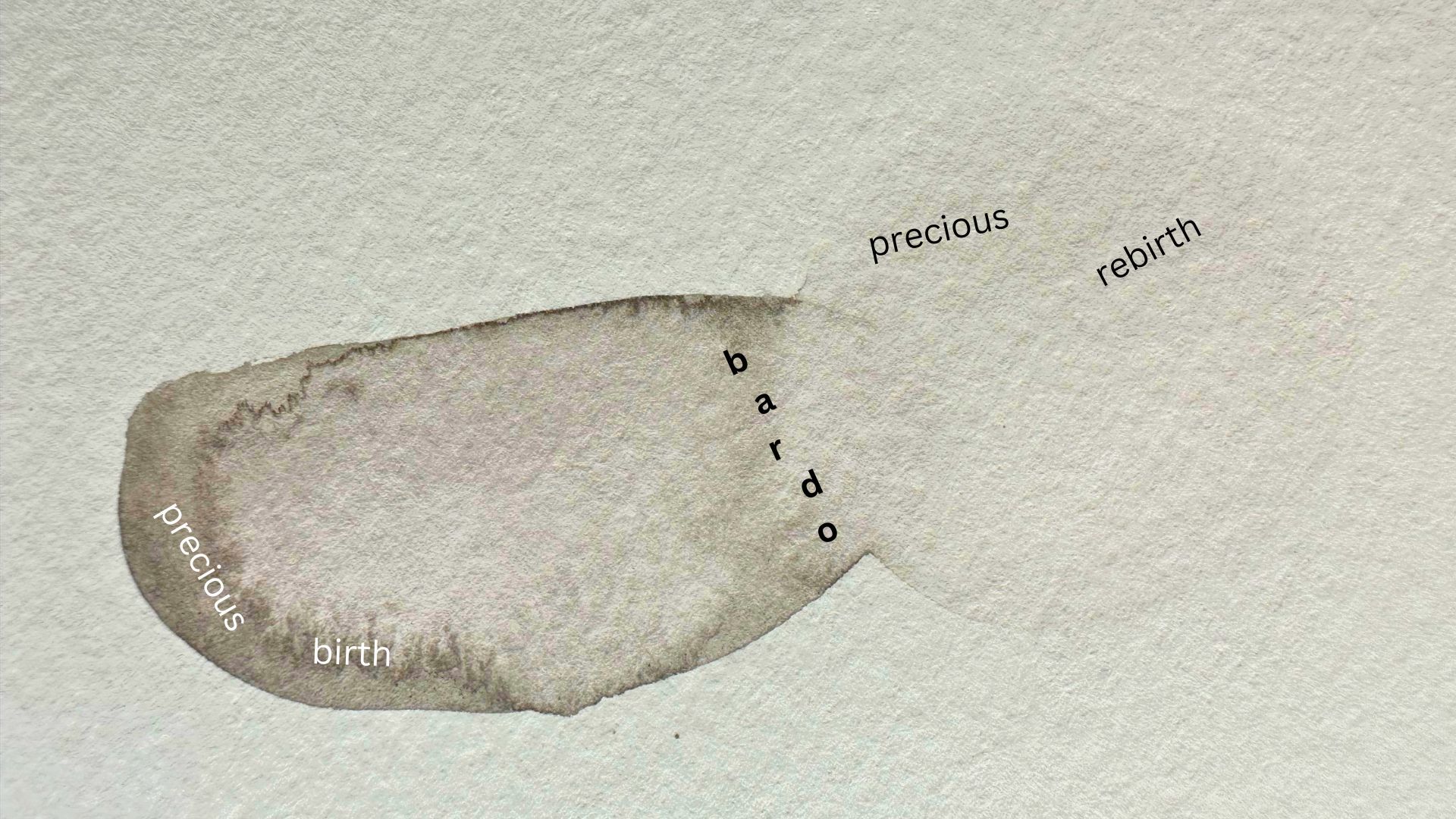

In Buddhism, after death there is the bardo, or the liminal state one travels through between birth and possibly rebirth. It is a state of searching, itself, where obstacles and distractions can pull you in and off course if you don’t hold the center lightly.

Bardos are everywhere, if we notice them.

In our precious human existence, uncertainty truly is our lifelong companion. Our propensities and capacities to search and search bring us ever closer into relationships with uncertainty in all its shapes – some fearsome, some luscious.

Tibetan Buddhist nun Pema Chödron reminds us that, “the central question of a warrior’s training is not how we avoid uncertainty and fear but how we relate to discomfort.” She’s talking about a metaphysical warrior – a tender huntress.

In this sense, our searches are not simply achey, pathetic holdovers until we’re fulfilled but themselves the most fertile training grounds for refinement of self. If you can find the lightness of the in-between, the pleasure of the sacred pause between having and not having, there is where liberation lies. This is, in fact, a choice.

So my intention as a tender huntress is to cultivate discernment in my searches, and self-awareness in my seeking. What am I really looking for? Why? Not all searches are the same. What matters and what definitely does not? Can I lean into the in-between, staying with myself more comfortably in the experience of not-having? What is my relationship with letting go?

I am working imperfectly but incrementally to sharpen my vision so I can see the texture of the search more clearly, not just the object or subject lurking at the end. In seeing our searches for what they are, we can choose for them to be spacious or audacious, decide to assemble a badass search party or not, and of course remembering that only some of it is up to us.

Some drops of longing make me feel alive. Too much swallows me up whole. I’m sniffing out that spot between inertia and freneticism. I work to stay dancing on the edge, trusting myself that if I topple over one way or another I’ll be able to climb back up to it.

In the 25 years since I lost that dazzling cuff, I’ve possessed and been dispossessed of several more ear cuffs, and maybe thousands of tangibles and intangibles. Did I lose them or did they lose me? Did our time together just…shift? Do I already have what I need?

Yes to all of it. Somewhere between the lost and found we find ourselves, able to trust the space that holds but doesn’t guarantee an outcome. This is faith, this is meditation, this is hunting practice.